INTRODUCTION

The novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious illness that emerged in Wuhan city, China, in late December 20191. COVID-19 is characterized by rapid transmission primarily through direct inhalation of infected droplets introduced into the environment via coughing, sneezing, and possibly secondarily through contact with the eye, nasal, and mucus secretions1,2. Likewise, travel history from COVID-19 dense areas and regions could increase the spread of COVID-19 to other regions3,4. Similarly, several other studies have reported the suspension of SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 viral agent, in the air for some minutes, thus explaining the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 across different regions5,6. In highly polluted areas, high concentrations of toxic pollutants in PM2.5 and PM10 or weather conditions may inhibit transmission7,8. Following SARS-CoV-2 infection, multiple symptoms can occur such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste, loss of smell, sore throat, etc.3,9. Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases are laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases that do not develop symptoms4. Arrays of evidence from literature report that asymptomatic COVID-19 cases could account for nearly 15–50% of total COVID-19 cases10-12. This, therefore, stresses that community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 could occur through symptomatic and asymptomatic cases enhanced via environmental and demographic factors.

There is a growing dynamism between personal, environmental, and community health, and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are of particular importance. It has been argued that effective responses to public health emergencies should rely on timely evidence-informed policy and practice geared toward disseminating the scientific evidence on ways to mitigate the pandemic – one of which is community engagement (CE)13-15. NPI measures such as regular hand hygiene practices, use of face masks in public places, and social distancing have been recommended as effective COVID-19 preventive measures16,17. To adopt these NPI measures in breaking the chain of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, active community engagement (CE) is quintessential18.

CE employs participatory communication, a community-development initiative that utilizes a bottom-up approach rather than the blueprint top-down approach in health interventions19. Previous studies have assessed the use of different CE strategies to improve populations’ health and social outcomes20-25. Each of these studies have identified that CE interventions refer to ‘meaningful citizen participation’ in which community members themselves drive any health intervention. In the description of the community-led EVD control efforts implemented by Sierra Leone’s Social Mobilization Action, Bedson et al.26 found that the involvement of local radio stations built CE among community leaders, EVD survivors, as well as members of the EVD response team26. Specifically, role model behaviors have been adopted to support community surveillance through a structured participatory dialogue which helped to reinforce trust in risk communication messages26,27. While these studies have been insightful, they do not provide professionals with sufficient information of CE interventions to contextualize for the implementation of CE interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is partly due to the novelty of the COVID-19 pandemic, and inadequate literature describing the relevance of CE to breaking the chain of COVID-19 transmission in community settings. A study of this regard is needed to identify how previous CE interventions led by community members themselves could be activated in breaking the chain of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in community settings. This study, therefore, aimed to describe the mechanisms of CE in the prevention and control of COVID-19.

METHODS

Study design, database search and article screening

A systematic review was conducted to support timely evidence on the control of the novel COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic review is a type of research that incorporates a rich body of evidence synthesis to produce relevant evidence on a subject matter of investigation28,29.

The research team documented a protocol prior to conducting the study. A systematic review of published academic literature was conducted in August 2021. The review specifically focused on the different ways through which CE had been adopted in different contexts for the prevention and control of COVID-19. Articles were required to describe at least one CE strategy. Criteria for including and excluding articles are as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for retrieved articles

The definition of CE adopted in this study considered the process by which community members actively coordinated themselves in the COVID-19 outbreak response efforts. These relate to the design, planning, implementation, and evaluation of specific disease-control activities.

The literature search was limited to three databases: Directory of Open Access Journals, PubMed, and Google Scholar. These databases were selected because they have higher indexation on many journals compared to other databases. Searches were conducted in English. In addition to retrieved articles, a search of the reference lists of the included studies was conducted. To expedite the literature search process, both authors participated in the database search reference list checking. All retrieved results were manually screened, and duplicates were removed. Thereafter, screening of article title, abstracts, and full texts were assessed by both authors, while a third party was invited to resolve discrepancies between both authors regarding the inclusion/exclusion of an article.

Predefined keywords were used for the search strategy. The Boolean operator “AND” was used to enhance the retrieval of relevant literature. Terms such as community participation, community involvement, community action, community initiatives, public participation, public engagement, public involvement, public action, public initiatives, and community efforts, have similar definitions to community engagement, therefore, they were also included in the search key words.

Keywords used in the literature search process

The search string was: [community participation OR community engagement or community involvement OR community collaboration OR grassroots engagement OR local participation OR citizen participation OR local group collaboration OR community contribution OR bottom-up contribution OR community network OR community groups OR community coalition] AND [COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus disease OR novel coronavirus disease OR coronavirus disease 2019] AND [prevention OR control OR hand washing OR social distancing OR masking OR testing OR isolation OR contact tracing OR case investigation OR sensitization campaigns OR screening OR quarantine OR safety measures].

RESULTS

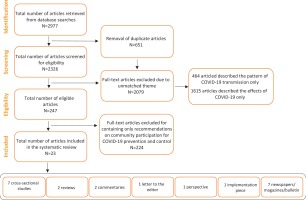

Overall, 2977 articles were retrieved from database searches, and 651 duplicates were removed. Thus, 2326 articles were screened for eligibility, out of whom 2079 were excluded due to unmatched content. Among them, 464 articles were excluded for containing information on the pattern of COVID-19 transmission only, and 1615 articles were excluded for describing the effects of COVID-19 only. As a result, 247 articles were eligible for the review. Among these, 224 full-text articles were excluded for detailing only recommendations on CE in COVID-19 prevention and control. Overall, 23 articles (7 cross-sectional studies, 2 commentaries, 3 reviews, 1 letter to the editor, 1 editorial, 1 perspective, 1 implementation piece, 5 newspaper articles, 1 magazine article, and 1 bulletin article) were included (Figure 1).

Table 2 shows the synopsis of literature retrieved from the literature search. Maclntyre et al.30 conducted a cross-sectional study that aimed to determine the trends in masking and other infection prevention behaviors during two periods of the COVID-19 pandemic, in cities in the United Kingdom and the United States, where a face mask was not a cultural norm. Another study found that compliance with the use of face masks contributed to a decline in COVID-19 cases in Melbourne and Phoenix. Poor handwashing and masking practices, however, contributed to a rise in COVID-19 cases in Sydney, London, and New York city30. A modelling study was conducted by Teslya et al.31 to compare the effectiveness of self-imposed prevention actions and government-imposed social distancing to mitigate, delay, or prevent COVID-19. It found that self-imposed measures were more effective and sustainable in reducing COVID-19 cases compared to short-term interventions31.

Table 2

Summary of literature retrieved from database search

A Letter to the Editor detailing the prevalence of formal, semi-formal, and informal organizations in the social control of COVID-19 reported the involvement of community committees in drug supply, screening, and distribution of COVID-19 information32. These measures have been helpful in breaking the chain of COVID-19 transmission. A study conducted by Hua et al.33 aimed at using firsthand Chinese social media and internet data and information to describe the chronological narrative of Wuhan and China. The study found that the achievement of China’s endeavor in the COVID-19 control effort was a blend of solid administration, and unconstrained local area involvement33. In a commentary, Bispo et al.34 described the community fight against COVID-19 in Brazil. The study reported that the populace’s investment is critical to enforcing social isolation and wearing of face masks, as well as in conducting effective contact tracing.

In their review, Al Siyyabi et al.35 described the three community approaches that exist in Oman and reviewed their role in preparedness and response strategies to COVID-19 pandemic. There, it was found that community organizations within cities and village initiatives created a platform for CE in ensuring community well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, the establishment of district health committees helped community leaders and groups to design pandemic action plans and strategies and implemented these using available local resources. Through volunteerism from local residents, community members were updated with COVID-19 data especially when lockdown measures were implemented35. In a primary research conducted on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria, and Pakistan, community leaders and residents applied telemedicine (using their phones) to contact healthcare providers36.

The engagement of slum communities in urban slums of São Paulo, Brazil, promoted adherence to COVID-19 safety measures in these communities. Despite their vulnerability to irresistible infections, community-wide implemented measures assisted with diminishing local area transmission of SARS-CoV-237. In a rapid evidence synthesis describing CE for COVID-19 prevention and control, the commitment of community leaders and stakeholders was basic to helping to debunk COVID-19 myths in community settings38. CE was enhanced through the creation of a two-way network of communication which aimed at building trust in the health system and avoiding misguided COVID-19 information in community settings. CE was, however, deterred through the absence of logical arrangement, and conflicting information that lacks evidence base39. To combat the spread of COVID-19 through community participation, Khongsai40 reported that community members were empowered as surveillance officers and health educators for the masses.

From a perspective that described the engagement of the local community in enhancing patient and staff experience during the COVID-19 pandemic in the YNHHS catchment area, school-age children designed cards that helped to reduce the sense of social isolation between patients, staff, and community members41. In an article that aimed to determine the implementation of case investigation and contact tracing in controlling COVID-19 transmission during the early stages of the US pandemic response, the engagement of community leaders helped to improve medication adherence and reduce the risk of onward transmission of COVID-1942. In an editorial that aimed to determine the role of health promotion in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, it was reported that local knowledge (through the engagement of community stakeholders) is required in the design of health promotion to facilitate early adoption of recommended COVID-19 preventive measures43.

To describe the COVID-19 pandemic response in selected countries across the globe, district heads coordinated the dissemination of information on COVID-19 risks and the adoption of telemedicine to reduce social contacts44. To describe the differences in COVID-19 spread, risk factors, and intervention activities in the Palestinian Territories, the collaboration between community stakeholders and World Health Organization personnel helped to reinforce COVID-19 risk communication through modern and traditional media, thus reducing COVID-19 morbidity and mortality45. To describe CE in COVID-19 prevention using experiences from the Kilimanjaro region of Northern Tanzania, it was found that support from religious leaders helped to reinforce maintenance of handwashing, disinfection of hands and surfaces, and social distancing46. To describe the role of CE in the prevention and control of COVID-19 drawing on insights from Vietnam, a cross-sectional qualitative study reported that members of community-based opinion groups helped to intensify COVID-19 risk communication efforts47.

Regarding the mechanism with which COVID-19 patients battled anxiety over tests and ostracism in their neighborhoods, community members set up the COVID Care Network (a caregiving and consultation service) and conducted COVID-19 sensitization campaigns48. In another piece on community-wide control of COVID-19 in Cape Town, South Africa, community members organized a Community Action Network where masks were distributed49. On Brazil’s COVID-19 outbreak response, Brazilian favelas initiated community-specific techniques for isolating suspected cases and reducing physical contact, and broadcast of jingles on COVID-19 prevention via audio and video modalities50. In a bulletin on the engagement of Mozambican workers returning from South Africa to check COVID-19 spread, volunteer Mozambican returnees contacted other returnees by phone, delivering key information on mandatory quarantine, COVID-19 prevention and management measures, and referral pathways, and obtained information on the manifestation of symptoms from each returnee51.

Through their organized groups, community volunteers in 42 case studies across the World produced and distributed PPE; and provided medical care and counselling support using ICT in ways that address psychosocial challenges and cultural and religious beliefs to overcome stigma and social isolation among COVID-19 positive cases52. In an article reporting the role of 10 young people leading the COVID-19 response in their communities in South Sudan, Peru, Kenya, Cameroon, Syria, Switzerland, Haiti, and Italy, youths fought COVID-19 misinformation and provided supplies to communities to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-1953. To describe adolescent girls’ response to local problems in COVID times in Vadodara City in Gujarat, the adolescents led the production of 5328 masks for frontline COVID-19 workers54.

DISCUSSION

This article aimed to describe the role of CE in the prevention and control of COVID-19 using a systematic review. This study exemplified CE in the context-based design of COVID-19 control measures such as screening, medication supply, handwashing, and dissemination of evidence-based COVID-19 information through community health committees. As described in one of the studies included in this review, CE is a continuum that begins with identifying the need for collaboration and resulting in community empowerment, especially in disease control39. The absence of sustained engagement of community members, traditional/opinion leaders, and community-based healthcare professionals, has been described as a major missing link in the control of EVD39. Since community members and their stakeholders are repositories of rich knowledge and experience regarding infectious disease outbreaks in their settings, they are therefore sustainable assets that should not be overlooked in any disease control intervention40,55. While promoting rigorous NPI measures in health facilities is of crucial need, the local community represents a potential source of spikes in national and global COVID-19 cases, if COVID-19 preventive measures are not implemented at the grassroots. Therefore, adequate integration of local communities is critical towards ensuring a more successful outbreak response.

From this review, we identified the role of CE in addressing COVID-19 infodemic and misinformation. Findings from China revealed that nearly one-third of community members proactively sought information on COVID-1933. If community stakeholders are not equipped with evidence-based knowledge of COVID-19, how then would they be able to disseminate this critical information to residents of their communities? Establishing partnerships with communities can help dispel COVID-19-related rumors and fallacies and alleviate unnecessary fear in community settings45,51,56. Likewise, it could help to improve trust levels of community members in government-led outbreak response efforts57. As a result, persons who manifest one or more COVID-19 symptoms would be linked to care, and many deaths would be prevented58. Thus, CE not only benefits the government and heath institutions, but also community members themselves. Therefore, collaboration with local authorities should be promoted by the government and other agencies in the COVID-19 outbreak response activities. Young persons in the community should be encouraged to volunteer, while community health workers should be empowered to conduct NPI trainings and COVID-19 sensitization campaigns for intending volunteers.

One of the studies included in the review reported that government-imposed COVID-19 preventive measures were short-term, and do not influence the attack rate of SARS-CoV-231. For instance, total nationwide lockdown could cause a reduction in social contact in communities, thereby postponing COVID-19 peak periods by about 5–8 months. However, government-imposed measures are only temporary and necessitate the implementation of more sustainable measures. Sustainable self-imposed measures are especially required following the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines. Self-imposed and/or community-imposed COVID-19 safety measures outlive the lockdown period and could delay peak periods in COVID-19 infection up to 12 months or beyond31. Due to pandemic fatigue, many individuals across the globe have thrown caution to the wind and COVID-19 enforcement efforts are no longer effective in the public58,59. Unfortunately, this disregard for the recommended measures contributed to the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. To promote global health, public health institutions and the government at large should intensify the promotion of self-imposed measures to delay the impending fourth wave. All that is required is sufficiently high coverage of self-imposed measures among community members, such as the use of face masks, regular handwashing, and/or social distancing, each having at least 50% efficacy in delaying viral replication.

From this review, we identified certain barriers to CE. These included the absence of logical arrangement and conflicting information that lacks concrete evidence38. These barriers could prompt distrust in implemented COVID-19 measures among community members. Reports from the EVD outbreak in Sierra Leone in 2015 revealed that distrust in the government and supporting institutions on NPI measures was a major barrier to the success of the EVD outbreak efforts60. To enhance CE, participatory communication between different partners and community members is crucial. Participatory communication entails an objective dialogue with a combination of actions to motivate local participation in its own development. To achieve participatory communication, channels of communication within each community should be open between community members, stakeholders, and partners55. Meetings could be scheduled on a regular basis to evaluate and modify COVID-19 preventive measures that are currently practiced. Community members could act as watchdog or surveillance officers in reporting individuals with COVID-19 symptoms or those with a travel history to a COVID-19 high-risk country, e.g. South Africa, Italy, or the United States61,62. Likewise, persons with no formal education in rural communities could be educated by volunteer community members through information, and education62.

Limitations

This study did not focus on the actors and mechanism of CE in the prevention and control of COVID-19, while the results of the identified studies are presented in narrative format. The absence of these details could have therefore masked certain important information. Despite these limitations, this study provides important evidence on the critical role played by community members themselves in breaking the chain of COVID-19 transmission.

CONCLUSIONS

CE ultimately has been proven as an effective method for sustained control of infectious diseases. To strengthen community-based response to pandemics, CE should be implemented through the following measures. Firstly, community members should be involved in the design of COVID-19 control measures in each setting. Secondly, volunteer young persons, with or without medical or allied qualification, should be mobilized to disseminate COVID-19 risk communication messages and promote acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine in their resident communities. Thirdly, pre-existing community health committees should be actively engaged in coordinating the COVID-19 outbreak response at the ward or district level. Social policies such as social distancing and use of face masks should be made with high stringency levels to ensure that community members contribute their quota towards reducing the transmission of COVID-19. Future longitudinal studies are required to determine the effects of community designed COVID-19 control measures in reducing the transmission rate of COVID-19 in community settings.