INTRODUCTION

Food is essential for life, but eating habits show wide variation between populations and individuals and in different chronological periods. Desire to eat is regulated by physiological factors, such as hunger and satiety, but is also strongly affected by food associated environmental stimuli1. Consequently, frequent exposure to high salt, fat or sugar foods increases their consumption, while studies suggest that obesity-susceptible populations are more sensitive due to neural function1. Obesogenic stimuli like unhealthy food marketing alter eating habits in the short-term after exposure, especially in vulnerable age groups such as school-age children2. The complications of unhealthy food and increased body weight are devastating in both adults3 and children4, increasing both morbidity and mortality. Therefore, investing in tools for creating good prototypes of healthy eating and body weight is challenging.

Over the centuries, many famous and inventive painters have depicted on canvas the body ideals, food, and the influences of the prevailing civilization and culture on dietary choices, including the pain and hunger caused by war. The power of art in offering valuable knowledge on food and eating habits over time is well expressed, as represented by the Wansink and Wansink5 survey. By collecting and comparing 52 paintings depicting one of the most famous meals in human history, ‘The Last Supper of Jesus Christ’ as narrated in the New Testament of the Bible, Wansink and Wansink5 calculated the per capita food ratio, and concluded that the serving sizes have increased linearly over the last millennium.

Since the Renaissance period there has been a parallel evolution of art and alimentary discoveries6, with Spain playing a catalytic role in both areas, due to its key geographical location. Throughout its history, Spain has been influenced by merchants from other parts of the Mediterranean, including the Phoenicians, who brought various sauces, the ancient Greeks, who brought olive oil, which became a key ingredient in the Spanish cuisine, and the Carthaginians and Romans who transferred the cooking methods of their cuisines7. Following the Colonial Wars and the discovery of the continent of America by Christopher Columbus in 1452, many new fruits, nuts, and vegetables, such as tomatoes, beans, and potatoes, were introduced to Spain, where they were grown or imported (e.g. cocoa) and incorporated in the Spanish cuisine8. The discovery of the potato was a milestone in the field of nutrition, and it has been one of the most important human foods for centuries. Originating in South America, it was introduced into Europe sometime in the 16th century. The first written evidence of the import of potatoes into Europe is a receipt dated 28 November 1567, issued by a potato exporter from the Canary Islands to an Antwerp merchant, and by the end of the 18th century, the potato had become very popular in France and neighboring countries9. Irish settlers were the first to introduce the potato to North America and cultivate it in the Londonderry area of New Hampshire in 1719.

The rise of middle class during the Renaissance resulted in an increase in the popularity of spices, and spice trading became the largest industry in the world10. Spices were condiments, used for flavoring, but they were also the main agents for conserving and preserving food. Spices, which are nowadays cheap and widely available, could at one time create enormous wealth. Spice trading created and destroyed empires, and even led to the discovery of new continents; America was discovered basically because Columbus was travelling ‘to the other side of the earth’, heading to India for spices. The discovery of America not only created empires, but also intensified the growing competition, sparking bloody conflicts over control of the spice trade. What is striking is that a small stick, such as cinnamon, cloves, or the seeds of a plant, such as cumin, would impel Europeans to embark on such tremendous, for that time, journeys. Disputes between European nations for sovereignty over the Spice Islands lasted for more than 200 years. As access to spices became easier, their value began to fall. Pepper and cinnamon are no longer luxury products and spices have lost their status and the charm that once made them worth as much as rare jewelry and precious metals, and responsible for circumnavigation of the globe11.

Europeans spread corn into Africa, and peanuts, beans, and tobacco into China. During the Renaissance, new standards in food preparation and preservation were created in Europe, while geographical exploration facilitated the spread of these new methods of food management12.

With the limitless eagerness to explore the world that characterized that period, and subsequent to the discovery of the new continent, the premises for a better life were established for people who travelled from one country to another, hoping to reach their dream. With their travels, they exchanged cultural characteristics, among the most significant of which were food products, cooking methods and eating habits.

The Fine Arts, and in particular painting, function as a means of disseminating information over the centuries, regarding, among other aspects of life, eating habits and body ideals. The purpose of this review was to compile a selection of paintings depicting eating patterns and body shapes from the 15th century to the present, and to explore the potential of the paintings to indirectly cultivate healthy eating habits and a balanced connection with body image. This potential is particularly pertinent in the present culture of instant digital communication of visual images via the social media and can be exploited imaginatively as the basis for health education in schools.

METHODS

Among the Fine Arts that extol beauty and aim to offer aesthetic pleasure, painting was selected for the purposes of this study. Artworks were selected in which food products, eating habits or body models were depicted, from the Renaissance period to the present. Several sources were used, starting with the magnificent exhibition of ‘Van Gogh Alive - The Experience’, where more than 3000 works of the great Dutch artist were presented through 3D representations13. The Museo del Prado in Madrid was the source of a large number of Spanish paintings from the 14th to the early 19th century14. Important collections of paintings by Italian artists were reached through the Brera Gallery, in Milan, Italy15, and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, which contains the largest collection from the Italian Renaissance period16.

The current review was performed under the auspices of the Hellenic Center of Education & Treatment of Eating Disorders (KEADD). Search for historical references was conducted at the National Library of Greece17, and at the libraries of the School of Fine Arts in Athens18, the Department of Fine and Applied Arts of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki19 and Fine Arts of the University of Western Macedonia in Florina20.

RESULTS

The Renaissance began in Italy, specifically in Florence during the 15th century, and spread throughout the Western world through the arts, literature, and sciences. During this time, art was dissociated from religion and became individualized. The concept of homo universalis was formed, that of a man who encompassed the ideals of the Renaissance: an inquiring and critical spirit, curiosity, and above all, a tendency to engage in every aspect of the arts and sciences. The term refers to the range or desired ‘universality’ of the polymathy that could be acquired21.

In 1480, Hieronymus Bosch portrayed the seven deadly sins, which, classified in increasing severity, are: sloth (acedia), pride (superbia), gluttony (gula), lust (lussuria), greed (avaritia), wrath (ira), and envy (invidia)22. Gluttony, or bulimia, refers to the consumption of extreme quantities of food, regardless of hunger, in a very short time, being first recorded as a problem in the 15th century23,24. Nowadays, it is known that irrational consumption of fatty meats combined with alcohol exerts a negative impact on health, increasing the risk of diseases with high morbidity and mortality, such as obesity25, cardiovascular disease26 and cancer27. Bosch, following the precepts of the Catholic Church, illustrated the dangers of overeating to health, while satirizing human sins, defects and insanity. Throughout human history, religion has been seen to establish food choices and eating habits, with both positive and negative effects28.

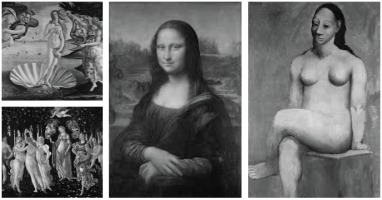

The Renaissance reintroduced classical themes to art. ‘La Primavera’, spring, through the eyes of Sandro Botticelli (1482) presents beautiful semi-covered female and male figures, accompanied by Zephyrus and Cupid, in a scene from classical mythology, surrounded by over 500 plant species and 190 different flowers29. The bodies appear exuberant, surrounded by a plethora of nature’s gifts30.

Painters, such as Perugino (1446–1523), Antonio Del Pollaiuolo (1433–1498) and Jan Gosaert (1478–1532), using classical art and naturalistic approaches, provide us with knowledge about the new religious and non-religious themes that appeared during the Renaissance31. During that period, both northern and Italian art presented the ideal human body similar to that of the ancient Greek classical period, completely symmetrical, reaching perfection. The ‘Nude’ was worshipped, and became central to artistic practice, as interest in classical antiquity was revived. During the same period, many artists focused on imprinting Christian worship on everyday life, resulting in the development of a newly vibrant representation of the human body. The ability to represent the naked body became a measure of the skill, intelligence, and originality of the artist. In parallel, portrayal of the naked body triggered controversies, especially in religious art, where the athletic, finely proportioned body, which for some communicated virtue, for others was considered to incite lust. A representative example of the creations of that period is the ‘Christ on the Cold Stone’ by the Flemish painter Jan Gossaert (1478), in which Christ is depicted as a handsome man with an athletic body32. In ‘The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian’ (1739), a work of the Italian painter Giovanni Batista, the saint, while suffering his martyrdom, has an unripe beauty and perfect physique, with golden hair and white skin33,34.

Meanwhile, Leonardo Da Vinci created the portrait of ‘Mona Lisa’, the most mysterious woman throughout the history of painting; the woman with the emblematic smile, dark hair and white skin, wearing a delicate dark dress and veil, and with her eyes beholding the observer35. This is a piece of art that combines elegance and beauty, without any hint of nudity, that is unceasingly admired and increases levels of aspiration and research interest36.

In the 16th century, ‘Mannerism’ was born in Spain, as a reaction to the Renaissance. The term is derived from the Latin manierus, meaning ‘way’, and its use prevailed during the First World War. This style triumphed throughout almost all of Europe from 1530 until the end of the 16th century37, providing indications of the dietary habits of the period. In the second half of the 16th century, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, in ‘The Four Seasons’ captured the seasonality of fruits, vegetables and plants in four profile portraits38, illustrating the capability of nature to transform according to circumstances, to ensure survival and to provide its commodities38. The distinction between urban and rural dietary patterns had been evident since the 16th century. In the cities, the products were distributed with relative ease and adequacy in the markets and the bazaars. A greater variety of products was available and more sophisticated cooking methods appeared in urban households, compared with the rural traditional fare. Urban residents, in addition to purchasing a wide range of fresh products, had the opportunity to consume ready-cooked food, bought from street vendors and open-air or covered shops. The administration of goods in the city market, however, could not always ensure the smooth circulation of food products. Frequent nutritional crises and inadequate distribution of products in the cities over that period are attested by accounts of the lack, adulteration, or high cost, of basic foods39.

Following that period, a new genre ‘Singerie’ emerged, of paintings of monkeys appearing in human costumes in anthropogenic environments. This fashion began in Flemish painting in the 16th century and was further developed in the 17th century, and is epitomized in 1600 by Franz Franken, with his work ‘Monkeys Playing Backgammon’, showing monkeys entertaining, while drinking wine and eating grapes40. The connection with the sensual Greek god Dionysus was emphasized, the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking and wine, of fertility, orchards and fruit, but also of festivity and the theatre, religious ecstasy and insanity41. The creation ‘Two Monkeys’, painted in 1562 by the Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel de Jongere, depicts two figures chained to the windowsill of a fortress in Antwerp overlooking the river Seld42. The oppression of the Flemish villagers by the Spanish occupation, and the prevalent hunger, are distinctly portrayed by the few walnut shells and the posture of the monkeys43.

At the end of the 16th century, different interests were aroused within Spanish artists, possibly inspired by exchanges with foreign painters and artistic development in a wider cultural environment. At this time, the ‘Still Life’ genre made its appearance, either autonomously or as a complement to more complex scenes. The term ‘still life’ describes a work of art that depicts a composition of inanimate objects, which may be either natural, such as flowers, fruit and vegetables, and dead animals (destined for the table), or artificial, such as vases, various utensils and books44. The Spaniards of the following century would become unsurpassable in this genre.

The 16th century was also an initial period of apotheosis of the fleshy female body. The portrayal of the naked body of the goddess Venus is a hymn to the classical beauty and purity of the soul and has been used by many artists to depict the beauty of nudity. Their paintings reveal the influence of the prevailing body standards of the time. In the mid 16th century, the artist Tiziano Vecellio emerged to shake-up the field of Art. Specifically, in his work ‘Venus Rising from the Sea’45, the female figure is depicted emerging from the sea in beautifully revealing nudity, without any attempt to hide anything of her well-endowed, shapely body. In Botticelli’s earlier painting of the same subject, ‘The Birth of Venus’ (c.1484–1486), the ideal of a well-shaped, curvaceous naked body prevails, inspired undoubtedly by the female bodies of that time, with bright colors and clear body lines46. Titian chooses to capture the figure of Venus based on later body standards, with more voluptuous curves and a firmer body type than all her previous depictions. It is of interest that during this period the first sugar factories were established in London, and the sausage industry was developed extensively in France, Germany and Italy47.

In the early 17th century, Caravaggio twice portrayed ‘Supper at Emmaus’, satirizing the different social classes of the time, through the supper of Jesus with the citizens of Palestine. The differences are evident from the contents of the table and the faces of those depicted48.

In general, the 17th century is defined by the Baroque movement, expressed in painting, but also in literature, sculpture, architecture, music, and politics. This century is also marked by the Dutch Golden Age, the Grand Siècle of Louis XI of France, the Scientific Revolution, and according to some historians, the General Crisis. The cultural backdrop of Spain during the Golden Age is characterized by mental vitality and intelligence, and a fashion for riddles and the illustrated puzzles that painters used to conceal hidden messages in their works49. The ‘Bodegón’ genre (literally ‘tavern’ in Spanish), or still life in general, became very popular in 17th century Spanish society as a non-religious type of painting, often with a hidden symbolic message within the theme presented. The main proponents of Bodegón were Diego Velazquez, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, and David Teniers. In 1620, Diego Velazquez painted ‘The Waterseller of Seville’ in which an old water seller gives a glass of water to a young boy, while a man behind them drinks from a mug. Some advocate that this painting may symbolize thirst, or, considering the allegory of the three ages presented, the mature man gaining knowledge. The tall crystal glass offered by the water seller reveals a fig through the transparency of the liquid, displaying the practice of that time of adding figs to the water to provide aroma or to add nutrients to prevent hunger and disease50.

In that period, kings lived in luxury and remained healthy by eating well, as characteristically presented in the famous painting by Velazquez, ‘The Maids of Honor’51, which portrays the Infanta Margarita Teresa, daughter of Louis IV and the new queen. One of the maids of honor is offering to the Infanta Margarita Teresa aromatic clay for calcium adequacy and proper development. During that period the Spaniards were defeated by the French, under King Louis XI, Spain fell under the occupation of the House of Bourbon52, and the Spanish bourgeoisie suffered from hunger as shown in the work of Bartolome Esteban Murillo, ‘The Young Beggar’53.

Two works that reflect the eating habits of the time in northern Europe are those of Jan Steen, ‘Wine is a Mocker’ (1668–1670) and Vermeer ‘The Girl with the Wine Glass’ (1660), in which the result of large amounts of wine consumption and its use for seduction are clearly depicted54. The red socks on the woman at the table in Steen’s painting indicate a woman of loose morals55. In general, Rembrandt, Paris Bordone, Lucas Cranach and Jan Steen were among the most important painters of 17th century Dutch art who captured prostitution in their works. Typical examples are the above two works, and another painting by Steen, ‘The Oyster Eater/Girl Offering Oysters’56.

At the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th, a new movement emerged that is considered spiritual, the ‘Enlightenment’57. During this era, an ordinary meal consisted of a piece of bread, an onion, a few olives or a piece of cheese or salted meat, legumes, greens and a little, if any, wine. Grain in the form of bread or porridge containing cereals, and cheese or butter, onions, and oil, are the staples, and water would be drunk. An exception to such daily meals would be made on major Christian holidays when meat would be the main dish. Kings and nobility of the time, meanwhile, would eat fresh eggs, figs and grapes and drink red wine. They did not consume any vegetables. The royal manual mentions ‘apotheosis of wheat, emphasis on meat and two main meals a day’. In 1760 the Industrial Revolution began, starting from Western Europe. New machines begin to be built, greatly facilitating farmers in cultivation, reducing working time and effectively contributing to increased production58.

The 19th century was marked by significant developments in science and technology. The mechanization of agriculture, the creation through breeding techniques of new and improved varieties of plants and animal species, and the evolution of the food industry all contributed to the upgrading of the quality, quantity and variety of goods used by man for his food58. The year 1809 marked a milestone in the history of food preservation. The French chef Nikola Appert announced the results of his research on the preservation of food in closed glass jars which he sterilized by immersion in boiling water, thus laying the foundations of canning12.

Edouard Manet, the forerunner of the ‘Impressionist’ movement, captured in his work ‘Α bar of the Folies-Bergère’, extolling modern life in Paris. Bottles of champagne, beer and wine can be seen at the bar, reflecting that alcohol was part of Parisian life59.

Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his brother Teo, on the occasion of his painting ‘The Potato Eaters’60: ‘I have tried to emphasize how these people eat potatoes in the light of the lamp, dig the earth with the same hands that now touch the plate. I'm basically talking about manual labor and how these people have earned their living honestly. (…) My painting praises manual labor’. Starting with the potato, as food for the poor and the afflicted, the painter of the peasants and the hard life, composed this, his favorite painting, in 1885. Its protagonists, the suffering faces and the hands, gnarled from hard work, of the peasants. All the creator’s touches are studied. ‘Smells of ripe cobs, potatoes, fertilizers and manure, because that's how the field smells’. The potato continues its course in history as the food of the poor, identified with human labor61.

At that time, in parallel, changes were being made in the depiction of the standards of beauty in Art; Alexandre Cabanel created a markedly different image of ‘The Birth of Venus’ from that of Botticelli. The change in body shape is evident in the late 19th century. As in ancient Greece, the portrait of the goddess of beauty reproduced in the Renaissance was of a female form with curves, refined, with symmetrically balanced proportions. In contrast, the 19th century artists continued to depict the model of the ideal woman with generous curves, but much more exuberant, with no particular balance of proportions62.

The 20th century was marked by the two World Wars but was also characterized by the progress of Science. At the beginning of the 20th century, nutrition science was still an ‘infant’, but growing rapidly. Many important advances in the field of nutritional knowledge were made between 1910 and 1960, with the discovery of various nutrients and elucidation of their biochemical relationship to human health58. In the 1900s with his paintings of ‘Mother and Child’ Pablo Picasso declares that there is no room for affection between the two because of hunger and poverty63. In 1936, Salvador Dali portrayed the ‘Soft Construction with Boiled Beans: Premonition of Civil War’, referring to the Spanish Civil War, which lasted until 193964. The winners of this civil war were Franco’s nationalist forces, openly supported by Adolf Hitler. The soft structure of the human mass is accompanied by a few boiled beans because, as Dali explains, no one could swallow all that subconscious meat without the presence of a few floured and melancholic beans. In general, Dali was pro-Hitler, and this is evident in his works of the late 1930s, ‘Autumnal Cannibalism’ and ‘The Enigma of Hitler’ (1939)65,66. In all three of his works, Dali presents hunger, fear and poverty in a brilliant way, depicting beans and bread67. These two comestibles are used during times of war, as legumes and flour are not perishable and can stand the test of time. Hitler’s occupation brought great hunger and misery to the people, and this is conspicuous in many works of artists of the time68.

Meanwhile, the era of great change in Art has arrived. Impressionism is considered the greatest movement of the 20th century. Physical standards take a different shape, with the Queens of Great Britain holding the lead in this change. The image includes a narrow waist (certainly helped by corsets) and an hourglass-shaped body, along with long hair, a sign of femininity that sets them apart from workmen. A characteristic work of capturing this body image is Manet’s ‘Olympia’69,70. Pablo Picasso is also considered an artistic leader of this era, demonstrating great zeal for the creation of a large number of works of art. Attention to the body, due to its monumental plasticity, appears to derive from the rediscovery of antiquity through the works in the Louvre. Picasso experiments with the work ‘Nude with Crossed Legs’ (1903), making the colors in the paintings open and lighter, while the body becomes firmer71. Finally, the discovery of the statue of Venus by Willendorf, found in 1908 in Australia, depicts a rounded pear-shaped body with sizeable breasts. In the famous statue of Aphrodite of Milos the body is curvaceous, but the breast is small72.

Nowadays, the food industry is based on the science of food technology that aims to keep raw food sustainable and to create a wide variety of foods with therapeutic characteristics or a high content of nutrients, known as functional foods and superfoods, respectively73. Life and art run in an extreme speed. Contemporary Art, affected by the technological revolution and digital technology, is constituted by artists who draw their inspiration from innovative science and advanced technologies, creating a multifaceted convergence between art, technology and science74. Refined food products have taken a significant place in peoples’ diet, resulting in obesity. At the other extreme, eating disorders preoccupy a significant proportion of mainly young people, influenced by the trend for fashion models to be tall and thin75. As a culmination, in Brooklyn, Kara Walker created a giant sphinxlike woman from Styrofoam coated in sugar76 and contemporary artists depict the female body in extremes: obese, very lean, dissolved by disordered eating77.

The creations of artists emanate myriads of stimuli that can influence the spectator at multiple levels. The journey through selected paintings of great artists from the Renaissance onwards, observed under the prism of exploration of the eating habits and definitions of beauty and body image throughout the ensuing periods, offers incomparable information (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The female body in the eyes of Boticelli (La Primavera), Cabanes (Venus), Da Vinci (Mona Lisa), Picasso (Woman with crossed legs)

The study and comparison of selected works of art, which project the different body ideals and food cultures across the centuries, can provide the stimulus for nutrition education. The living circumstances of their times influenced the artists, who depicted real life as it was, but also or allegorically. Wars, hardship, hunger, and the misery of nations, but also the extreme affluence of the royalty and nobility fill the scenes of the various paintings. Some artworks depict populations poor and oppressed, but who, nevertheless, observed healthy eating habits, in terms of today’s definition78. The fruits and vegetables that high society would reject were depicted in their daily diet, with vegetable soups, dairy products, herbs, nuts and fruit filling the tables of the villagers. The lower societal classes often had a better-quality diet by cultivating and consuming their seasonal products. Nowadays, ironically such ‘health food’ is the more expensive, while less nutritional refined products cost less79.

The fine arts, including painting, have the potential to heal and to educate, recognized in its Constitution by the World Health Organization (WHO), approaching health and disease holistically80. Writing, painting, music, dance, singing and chants have been used throughout history as a healing technique81.

Music, the most extensively researched art medium, has been shown to be beneficial in soothing anxiety and depression, and restoring emotional balance82,83. Research on the effect of music on pain has revealed its beneficial attributes, especially when the participants are singing84,85. Better outcomes of surgery are observed86, with reduction of the duration of hospital stays, as a result of the of patients listening to music87.

The visual arts, such as textiles, painting and pottery, have been shown to increase the overall health of cancer sufferers, by increasing optimism, socialization, self-esteem and self-expression, especially in high-anxiety periods such as during chemotherapy88. Women with cancer felt more relaxed and creative when painting themselves on canvas or engaging in yoga and meditation89.

Viewing visual art expression via television, films and on digital devices, in general has been shown to influence perceptions of health and well-being90,91, with a considerable impact of social media on people’s psyche. A variety of digital applications, such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter, have invaded people’s lives. They can also function as modern channels of art distribution to the public, influencing the emotions, but also daily life, lifestyle, dietary patterns, and body image.

The ramifications of these patterns, with the emotions evoked, are extensive and the impact on the online audience is undeniable, but controversial, with enjoyment and positive effects, but also possible negative psychological consequences, leading to depression, insecurity and feelings of inadequacy and emptiness92. Through these digital platforms, the viewer is given the opportunity to express his/ her inner world and, in turn, integrate his/her art – paintings, photographs or videos – into the contemporary art of the 21st century93-95.

As image is the basic principle of the social media, the users are set up to present themselves without imperfections. A vicious circle of comparison leads to altered reactions and behavior, which can be very arduously for anyone who feels ‘incompetent’ if unable to adapt to the standards of the other users. Currently, media analysts and anthropologists support the overall view that social sharing through these platforms often results in feelings of dissatisfaction. A large proportion of people using the social media desire a lifestyle different from their own, and search for it in the online world. The link between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes and the expansion of social media use is undeniable96. Body image concerns are increasingly affecting a high proportion of people negatively, mainly children and adolescents, and this effect is closely related to the use of social networking sites97.

The modern forms of visual art should not be discounted, but digital techniques should be used to benefit the mental and physical health of the users. Their power to spread vast amount of visual information in seconds could be used to educate the users about healthy lifestyles, balanced body and mind, and healthy eating, and such messages should be guided by health professionals. A concerted effort by artists and health professionals could offer online artworks, where the ideal body is the healthy body, and healthy eating is not restricted eating but a balanced diet98.

Art, as seen from this review, dismisses all stereotypes, and study of painting through the centuries confirms that there is, in fact, no fixed standard, and that regardless of whether the body is slender or voluptuous, strong or languid, lean or with rich curves, it has always provided an ideal of beauty.

A route for spreading educational art for promotion of discourse on eating habits and body image could be via modern visual arts and the social media, aimed at relieving stress and anxiety regarding body and food. The aim would be to alleviate distress, as it will not promote the ‘perfect’ but the ‘real’, through the contemporary channels of circulation of information, with their immediacy and constant updates99.

CONCLUSIONS

The interventions that improve health through art are largely undocumented, but the results so far are largely promising, thus building the foundation for ongoing research on this topic. Art has already been shown to be a promising tool for complementary treatment of disease or alleviation of symptoms in a range of conditions, such as psychological disorders, anxiety and stress, metabolic disorders, sleep disorders, and cancer. It can facilitate the patient in communicating his/her feelings when encountering barriers in verbal communication, the creative process being beneficial for mental health. Although in its infancy, research on the potential of the use of art in health preservation and the prevention and treatment of disease, shows promise. Αt an even earlier stage of development and application is the use of art in nutrition education and therapy, including the prevention and treatment of eating disorders. With confidence in the field of scientific evolution, art can be incorporated to facilitate nutritional education. The combination of a healthy diet and a healthy body image will have equally promising results regardless of gender, age and other factors that may play a role in the treatment of any disease. The use of paintings to generate discussion on food and body image can be incorporated in school health-education programs.