INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use is recognized as a significant risk contributing to various health ailments1. Extensive documentation exists regarding the detrimental health impacts of smoking2. Smoking is biologically associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke, coronary heart disease, and lung cancer3,4. Additionally, it correlates with selfreported declines in overall health, compromised mental and physical well-being, and frequent limitations in activities4. In recent years, tobacco use has been linked to various psychological conditions such as anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit or hyperactivity disorder5. Particularly in adolescent boys, smoking has been associated with dissatisfaction with life, feelings of isolation, and subsequent anxiousness or depression6. Based on the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), approximately 22 million individuals (23.0%) in Bangladesh are presently using various tobacco products. About 12.0% of those aged 15–24 years and 26.0% of individuals aged 25–44 years in the general population, are involved in tobacco consumption7. Research derived from the Demographic and Health Survey indicated that the prevalence of smoking among Bangladeshi men stands at 60%8. The continuous rise in tobacco users is attributed to the affordability of tobacco products, insufficiently robust tobacco control regulations, and ineffective enforcement of existing rules9. Undergraduate students face increased smoking risks due to their youth, easy accessibility to tobacco items, close relationships with peers who smoke10, and the influence of smoking friends and parental habits11. For some students, smoking may represent a symbolic entry into adulthood, leading to a higher likelihood of smoking compared to the general population12. Senol et al.13 reported that among initially non-smoking university entrants, approximately one-third adopt regular smoking by the end of their academic tenure. Additionally, Masjedi et al.14 found that students in their final year exhibit significantly higher smoking rates compared to those in their first year of studies.

The evidence highlights a well-established link between smoking and mental health15. However, establishing causality or determining the direction of this association poses challenges for various reasons15. Firstly, poor mental and physical health might prompt smoking as a form of self-medication16. Nicotine’s impact on neurotransmitters, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and dopamine, can result in increased energy, positive reinforcing effects, and reduced feelings of anxiety and depression16. Secondly, smoking (nicotine) might contribute to deteriorating mental health through neurotransmitter pathways. Moreover, given that cigarettes contain more than 7000 harmful chemicals, including 70 known carcinogens, smoking significantly impacts health15. The connection between poor physical health and mental well-being could be due to the discomfort and limitations that come with physical illness15. Finally, the relationship between smoking and health might not be entirely causal, as certain unobserved factors, such as personal characteristics, social settings, and genetic predispositions, might concurrently influence both smoking habits and poor mental and physical health17. In essence, the relationship between smoking and mental health could be simultaneous and bidirectional. Our research aims to address these complexities, focusing on a public university in the northern district of Bangladesh. This study intends to explore both the prevalence and the impact of smoking on the mental health of district-level university students in Bangladesh.

METHODS

Study design and sample

A cross-sectional study was conducted among university students in Dinajpur district, focusing on Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University (HSTU) as the study area, with male students from that university as the study population. A preliminary examination was conducted on a 5% subset of the projected sample size at HSTU to assess the clarity of inquiries and respondents’ attitudes towards both the questions and the interviewer. All the female students were excluded from this study. A two-stage sampling method was employed to select samples. In the first stage, 15 departments were chosen from the 45 departments of HSTU using a simple random sampling method. Subsequently, participants were selected from these chosen departments in the second stage using probability proportionate to size sampling (PPS). To determine the ideal sample size n for this study, Yamane’s simplified sampling formula was used18:

where, Z=1.96, was employed, assuming an unknown population proportion p set at 50% with a margin of error d set at 3.5%, resulting in an approximate requirement of 294 participants. However, we finally collected data from 300 students for this study. The response rate approached 100%.

Data collection

A self-structured questionnaire was used to collect data through face-to-face interviews. Data collection took place between 1 August and 30 September 2023. All full-time undergraduate and postgraduate students were included in this study. During the face-to-face interviews, printed questionnaires were provided to the participants along with a brief explanation of the questionnaire and the aim of the study. Every student had the choice not only to abstain from participating in the entire interview but also to omit specific items from the questionnaire. Qualified data collectors conducted voluntary interviews with the participants.

Operational definitions

In this study, a student is considered a regular smoker if they smoked at least one cigarette per day for a period of six month. Additionally, a student who had smoked previously but had stopped at least a year before was considered as a non-smoker19. The smoking behavior of the students was assessed based on factors such as smoking time, residence, monthly expenditure, and so on. Furthermore, the mental health of the students was assessed through questions such as: ‘How is your health?’, ‘How many hours you sleep in a day?’, and ‘Do you have any complex disease? If yes, what types of disease?’, ‘Have you noticed any changes in your mental health since you started smoking?’, ‘Do you think your smoking has affected your ability to concentrate?’, and so forth.

Data management and statistical analysis

The data underwent coding and analysis using statistical software such as SPSS (version 26) and R-software (version 4.0.1). Prior to analysis, a comprehensive review and cleaning of the dataset were performed to ensure accuracy by rectifying errors and eliminating inconsistencies. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means and standard deviations were used to summarize the sample characteristics, smoking patterns, and mental health aspects. The relationship between smoking status and demographic or mental health factors was explored using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for continue variables. Binary logistic regression was used to identify the potential factors of smoking habits among students, employing only significant factors identified in the chi-squared test. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with a 95% CI were used to measure the strength of the relationship between them. Results were considered statistically significant at a level of p<0.05.

RESULTS

In our analysis of 300 male students, we found a 59% smoking prevalence. Science and Engineering faculties showed higher rates (37% and 31%, respectively) compared to Fisheries, Veterinary, and Animal Science faculties. Religion did not significantly affect smoking, but Hindu students showed a prevalence of 66.7% versus 57% for Muslims. Students living in university halls (65.1%) smoked more than those at living at home. Those from separated families (62.3%) smoked more than those from intact families. Students whose father’s education level was a graduate or higher secondary smoked more (69.5% and 67.8%, respectively) than those whose father’s education level was primary or secondary (44.2% and 48.3%, respectively). Students who spend over 6000 BDT (1000 Bangladeshi Takas about US$8.5) per month smoked more (75.8%), and those with more than 3 siblings smoked more (67.6%). Our study underscores significant associations between smoking and fathers’ education level, residence, number of siblings, and monthly expenditure at HSTU (Table 1).

Table 1

The sociodemographic characteristics of students categorized by smoking status (N=300)

| Characteristics | Smoker n (%) | Non-smoker n (%) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 177 (59) | 123 (41) | |

| Faculty | 0.120 | ||

| Agriculture | 29 (72.5) | 11 (27.5) | |

| Computer Science and Engineering | 25 (59.5) | 17 (40.5) | |

| Total | 177 (59) | 123 (41) | |

| Business Studies | 17 (56.7) | 13 (43.3) | |

| Fisheries | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | |

| Veterinary and Animal Science | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) | |

| Engineering | 31 (66.0) | 16 (34.0) | |

| Science | 37 (52.1) | 34 (47.9) | |

| Social Science and Humanities | 20 (69.0) | 9 (31.0) | |

| Religion | 0.164 | ||

| Muslim | 135 (57.0) | 102 (43.0) | |

| Hindu | 42 (66.7) | 21 (33.3) | |

| Residence | 0.04 | ||

| Mess | 80 (53.7) | 69 (46.3) | |

| Hall | 95 (65.1) | 51 (34.9) | |

| Home | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Family type | 0.124 | ||

| Intact | 58 (53.2) | 51 (46.8) | |

| Separated | 119 (62.3) | 72 (37.7) | |

| Father’s education level | 0.015* | ||

| Primary | 19 (44.2) | 24 (55.8) | |

| Secondary | 28 (48.3) | 30 (51.7) | |

| Higher secondary | 59 (67.8) | 28 (32.2) | |

| Graduate | 30 (56.6) | 23 (43.4) | |

| Postgraduate | 41 (69.5) | 18 (30.5) | |

| Monthly expenditure (BDT) | 0.000* | ||

| <4000 | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | |

| 4000–6000 | 57 (43.8) | 73 (56.2) | |

| >6000 | 116 (75.8) | 37 (24.2) | |

| Number of siblings | 0.006* | ||

| <3 | 85 (51.8) | 79 (48.2) | |

| ≥3 | 92 (67.6) | 44 (32.4) |

The analysis of continuous demographic variables revealed that smokers had a mean age of 23.03 ± 1.76 years, slightly higher than non-smokers at 22.48 ± 1.68 years, which was statistically significant (Table 2). Regarding body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), smokers averaged 23.45 ± 2.86 while non-smokers averaged 23.96 ± 2.32, indicating that smokers BMI was slightly lower, but the standard deviation was comparatively higher.

Table 2

The sociodemographic profiles of the students based on smoking status (continuous variables)

| Variable | Smoker Mean ± SD | Non-smoker mean ± SD | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (Range: 19–27) | 23.03 ± 1.76 | 22.48 ± 1.68 | 0.046* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.45 ± 2.86 | 23.96 ± 2.32 | 0.095 |

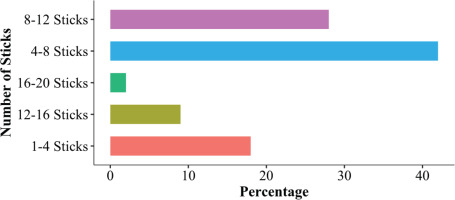

The average number of cigarettes smoked per day by students (Figure 2), revealed that 18% of smokers consumed between 1–4 sticks per day. The highest percentage, 42%, smoked between 4–8 sticks per day. Those smoking 8–12 sticks constituted 28%, while 9% smoked between 12–16 sticks daily. The lowest percentage, 2%, smoked between 16–20 sticks per day on average.

We explored mental health aspects associated to smoking status. Among participants, 139 smokers (54.1%) reported good health, contrasting with 118 non-smokers (45.9%), a significant difference (p<0.001) (Table 3). Sleep patterns revealed that 130 smokers (56.3%) slept 5–8 hours, differing from 101 non-smokers (43.7%), and notably, 17 smokers (85%) versus 3 non-smokers (15%) slept <5 hours (p<0.05). Regarding complex diseases, 15 smokers (78.9%) had such conditions compared to 4 non-smokers (21.1%), lacking statistical significance (p=0.074). Specific diseases between both groups also show no significant differences (p for ‘Other’=0.868). Assessing changes in mental health since starting smoking, 26 smokers (26.5%) noticed changes versus 72 non-smokers (23.5%), without a significant difference (p=0.686). Similarly, effects on concentration after smoking exhibited no notable difference (p=0.268). However, perceptions of smoking’s impact on mood and anxiety significantly varied, with 58 smokers (58.5%) feeling affected compared to 41 non-smokers (41.5%) (p<0.001). Long-term concerns about mental health effects due to smoking, reported eating disorders, and intentions to quit smoking showed no significant differences (p=0.762, 0.179, and 0.116, respectively). This data reveals diverse mental health aspects, behaviors, and perceptions between smokers and non-smokers, highlighting significant differences in reported health, sleep patterns, and perceptions regarding smoking’s impact on mood and anxiety.

Table 3

Association of mental health indicators with the smoking status of the respondents

| Variable | Smoker n (%) | Non-smoker n (%) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| How is your health? | 0.000* | ||

| Good | 139 (54.1) | 118 (45.9) | |

| Poor | 38 (88.4) | 5 (11.6) | |

| How many hours you sleep in a day? | 0.041* | ||

| 5–8 | 130 (56.3) | 101 (43.7) | |

| <5 | 17 (85.0) | 3 (15.0) | |

| >8 | 30 (61.2) | 19 (38.8) | |

| Do you have any complex disease? | 0.074 | ||

| Yes | 15 (78.9) | 4 (21.1) | |

| No | 161 (58.1) | 116 (41.9) | |

| If yes, which types of disease? | 0.868 | ||

| Cancer | 1 (100) | 0 | |

| Lung disease | 1 (100) | 0 | |

| Diabetes | 1 (100) | 0 | |

| Other | 12 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Have you noticed any change in your mental health since you started smoking? | 0.686 | ||

| Yes | 26 (70.3) | 11 (29.7) | |

| No | 72 (66.7) | 36 (33.3) | |

| Do you think your smoking has affected your ability to concentrate? | 0.268 | ||

| Yes | 30 (75.0) | 10 (25.0) | |

| No | 70 (65.4) | 37 (34.6) | |

| How do you think smoking affects your mood and anxiety levels? | 0.011* | ||

| Yes | 58 (77.3) | 17 (22.7) | |

| No | 41 (57.7) | 30 (42.3) | |

| Do you perform any physical activity? | 0.103 | ||

| <30 minutes | 28 (53.8) | 24 (46.2) | |

| ≥30 minutes | 136 (66.0) | 70 (34.0) | |

| Are you concerned about the long-term effects of smoking on your mental health? | 0.762 | ||

| Yes | 38 (69.1) | 17 (30.9) | |

| No | 60 (66.7) | 30 (33.3) | |

| Have you felt any eating disorder after smoking? | 0.179 | ||

| Yes | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | |

| No | 89 (66.4) | 45 (33.6) | |

| Do you have any intention to quit smoking? | 0.116 | ||

| Yes | 39 (60.9) | 25 (39.1) | |

| No | 60 (73.2) | 22 (26.8) |

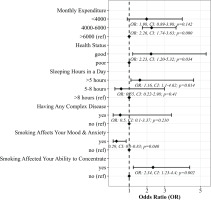

To explore the potential factors of smoking, we used a binary logistic regression model, and the results are shown in Figure 1. In doing this, we only considered six significant factors that were found in our previous analysis such as student monthly expenditure, health status, sleeping hours per day, having any complex disease, smoking affecting mood and anxiety, and smoking affecting concentration. Certain factors were identified to negatively influence students’ mental health. Students with a monthly expenditure between 4000–6000 BDT were approximately 2.26 times more likely to smoke (AOR=2.26; 95% CI: 1.74–3.63) compared to those with >6000 BDT. Those reporting poor health were 2.23 times more likely to smoke (AOR=2.23; 95% CI: 1.20–5.32) than students in good health, potentially due to smoking’s impact. Interestingly, students sleeping <5 hours per day were 1.16 times more likely to smoke (AOR=1.16; 95% CI: 1.1–4.62) than those sleeping >8 hours. Additionally, students who believed smoking affected mood and anxiety were 29% less likely to smoke (AOR=0.29; 95% CI: 0.1– 0.83) than those who did not share this belief. Conversely, respondents believing smoking affected their concentration were 2.34 times more likely to smoke (AOR=2.34; 95% CI: 1.23–4.4) compared to students who did not hold this belief.

DISCUSSION

This study primarily aimed to investigate the relationship between smoking behaviors and mental health outcomes among the student population within a specific geographical and educational context. The prevalence of smoking among the district-level university students was 59.0%, which is higher than among university students in the Sylhet division (37.0%)19. According to the GATS report, the overall prevalence of smoking in Bangladesh is almost 23.0%7, indicating that the prevalence of smoking is higher among the university students than among young adults. Another study on medical students in Dhaka found a higher prevalence of smoking (68.0%) than ours20. However, the smoking prevalence among the students found is higher compared to India (20.4%)1, Pakistan (26.1%)21, and Nepal (33.6%)22. These results indicate that the prevalence of smoking is higher in Bangladesh compared to other Southern Asia countries. This study was found that students living in hall were more likely to smoke than those living elsewhere, while another study found that smoking prevalence is higher among students living away from home19. Additionally, smoking prevalence is comparatively higher among students from urban areas than among those from rural areas23. These results indicate that when students live away from home or away from their parents, they have a higher chance of being smokers. This study also revealed that students from separated or single families had a higher chance of being smokers than students from joint families. This study also revealed that the students who spend more money have a higher chance of being smokers, which is similar to another Bangladeshi study19. This generally happens due to greater economic status, as students with more money in their pocket can engage in higher-risk behaviors19. Similar findings were found in EI Salvador study, which indicated that higher smoking rates are associated with good economic status24, as well as in studies conducted in India1 and Nepal22, which found that greater economic status is an important factor for smoking among young adults and students, respectively. However, students who stay at home with their families have fewer opportunities to take part in high-risk behaviors. The finding of this study showed that students whose father’s education level is higher tend to smoke more than those with a father’s education level that is lower, which is similar to the another study19. Even though the higher educated fathers are more concerned about smoking hazards than less educated fathers, some researchers have shown the importance of parent’s education. Parents’ lack of education might contribute to this issue; they might be unaware of the risks associated with smoking, which could reduce their likelihood of advising their children against it. The overall health of smokers is comparatively poor according to our findings, which is similar to other studies25. Toghianifar et al.26 found that compared to non-smokers, smokers generally scored lower in aspects of general health, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health. Recent quitters displayed notably enhanced role-emotional and mental health compared to those who persisted in smoking or those who started smoking. The study also highlighted that smoking heightens the risk of non-communicable illnesses like cancers, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases27. Additionally, adults with a higher incidence of health issues often exhibit a lower quality of life, leading to increased odds of depression and more pronounced fatigue28. Students who slept <5 hours per day had a higher risk of smoking than those who slept >8 hours, and similar results were found in the United States29. Sleeping <5 or >8 hours/day was associated with an increased risk of cigarette smoking. In a study conducted in 2010 in Iran, sleeping <6 hours or >9 hours per day showed a link to an increased risk of cigarette smoking. No study has indicated that maintaining a regular sleep pattern is positively linked to smoking. Students with such disorders might exhibit regular sleep patterns and longer durations due to the nature of the illness or medication effects30. Additionally, in a separate cross-sectional study, insomnia was found to be positively associated with smoking in adults31. On the other hand, this study also found that smoking has affected the ability to concentrate, which means that it improves concentration. The top reasons individuals report for smoking are stress relief and enjoyment, with roughly half of smokers mentioning these motives32. Additionally, reasons such as weight control, improved concentration, and socializing are also frequently mentioned among smokers33. Smoking has an effect on mood and anxiety level. We showed that smoker’s mood and anxiety level change are affected more than those non-smokers. One study indicated that females tended to have a negative mood, aligning with earlier findings indicating that a higher likelihood of negative mood might increase the risk of females starting to smoke34. Intriguingly, while depression symptoms might be more prevalent in adolescent females compared to males, a combination of depression and irritable mood appears to be more frequent among males34. Another research revealed that as the severity of smoking dependence rose, the psychosomatic symptoms related to anxiety, insomnia, and depression also increased35. The study also found that smoking had also influence on the eating habits of the students. This finding is similar with another study, which found that women with eating disorder had a high-risk of smoking36. They also said that smoking and eating disorders were related to impulsive personality traits.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first study conducted in a district-level university in Bangladesh. The study provides a focused exploration of the smoking-mental health relationship using a cross-sectional design, offering insights into smoking habits and mental health among district-level university students in Bangladesh. However, it has some limitations. The reliance on self-reported data poses risks of recall bias, and the cross-sectional design of the study may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between smoking and mental health outcomes. Additionally, the exclusion of female students from this single public university setting limits the findings’ broader applicability. Since the study focuses on a specific district-level university in Bangladesh, the results may not be representative of the broader population in Bangladesh or other regions. Lastly, the study’s reliance on a single university setting may limit the diversity of the study population.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides valuable insights into the interplay between smoking habits and mental health among district-level university students in Bangladesh. The findings underscore a concerning trend: a considerable number of students initiate smoking during their university years. The research indicates a notably higher prevalence of smoking among the district-level university students. Furthermore, smoking habits are highly correlated with monthly expenditure, father’s education level and residence type. These smoking behaviors significantly impact students’ mental health, contributing to complex diseases, concentration issues, altered mood and anxiety levels, eating disorders, and disruptions in their academic pursuits and physical well-being. To address these challenges, proactive measures are crucial. University authorities should implement awareness programs, workshops, smoking cessation initiatives, peer education, counseling, and prevention strategies to educate students about the hazards of smoking and promote a tobacco-free campus. These insights could serve as valuable assets in policymaking endeavors, particularly those aimed at fostering tobacco-free environments within academic settings.