INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has significantly affected the lives of healthcare workers1. Studies have consistently shown that the psychological morbidities among healthcare workers (HCWs) have increased significantly1,2. One of the major factors causing stress and psychological morbidities among HCWs has been shown to be the experience of COVID-19-related stigma from the public, neighbors, and friends that healthcare workers experienced because of the nature and place of their work3. The major barrier in the assessment of stigma among HCWs, especially during the early period of the pandemic, has been the unavailability of validated scales exploring the experiences of COVID-19-related stigma among healthcare workers. Due to the immediate nature of the study, we prepared a stigma scale based on a previously published scale which was validated to study stigma among nursing staff during the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak and explored COVID-19-related stigma among various sections of healthcare workers4-8.

The objective of the current study was to assess the psychometric properties of the newly formed COVID-19-associated stigma scale, specifically its factor structure, and to assess COVID-19-related stigma among HCWs.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study among healthcare workers from India using online self-report questionnaire designed in Google Forms. Separate questionnaires were prepared for doctors, nurses, and dialysis staff. The study questionnaire includes demographic information as well as a stigma scale based on a questionnaire developed to assess stigma among nursing staff during the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak4. The sole difference was that the pandemic’s name was changed from MERS-CoV to COVID-19. Each of the 13 statements on the scale is assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. The total score ranges 0–52, with a higher score suggesting that healthcare workers reported more stigma. The questionnaire was distributed via social media channels to people who work in healthcare settings. The participants were encouraged to forward the survey to other members of the same professional group working in their hospitals. Participation in the voluntary survey was deemed as informed consent. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The data collection was done between April 2020 and August 2020. A copy of the survey instrument can be found in the Supplementary file.

Face validity of the experimental version of the stigma scale was pretested on a sample of 20 HCWs to assess the cultural acceptability and the understandability of the items. Participants reported no unclear or difficult to understand items in the scale. Content validity of the experimental version of the stigma scale was assessed by involving two experts who were familiar with psychometric methods for the assessment of content validity. The scale was modified according to their inputs regarding wording, grammar, clarity, relevance, understandability, and relatedness to Indian culture.

The structural validity (construct validity) of the stigma scale was determined using exploratory factor analysis. A total of 662 individuals’ completed forms of the 13-item COVID-19 stigma measure were evaluated. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 23 was used for the analysis (IBM Corporation, New York). Assumptions for the exploratory factor analysis were analyzed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test (for sample size adequacy), and the Bartlett test of sphericity (for inter-item correlation significance). Factor extraction was conducted using principal component analysis (PCA) and varimax with Kaiser normalization rotation method was used. The reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach α, showing how much each of the items in the questionnaire is related to the overall result.

RESULTS

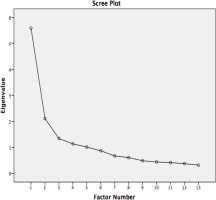

The present study received 662 complete responses. The majority of the study participants were aged 21–40 years (92.3%), married (67.4%), female (60.7%), and having work experience between 1 and 10 years (65.2%). A significant proportion of the respondents were staff working in dialysis units (50.6%), followed by nurses (27.5%), and doctors (21.9%). Among the study participants, 20.8% had exposure to COVID-19, 18.9% had a history of quarantine, and 70.8% were staying with their families. Among the study participants, 408 (61.6%) had significant COVID-19-associated stigma. The mean stigma score for the participants was 26.95 (SD=8.33; range: 0–52). The current study’s sample size was substantially larger than the suggested sample size of 195 (i.e. 15 participants per item for 13 items). This adequate sample size was confirmed further using the KMO test measure, which was 0.850. The bulk of the correlations found between each of the 13 items were statistically significant (p<0.05) (Table 1). The Bartlett test for sphericity was likewise found to be statistically significant (χ2=3132.985; p<0.001). The eigenvalues for the five extracted factors were greater than one, according to the principal component analysis; the Scree plot is shown in Figure 1. These variables explained 72.79% of the total variation. Table 2 displays the component factor loadings for each of the 13 items on the COVID-19-related stigma scale. The factor reliability for the extracted factor was also found to be good with Cronbach α=0.843.

Table 1

Inter-item correlation matrix, between the 13 items of the scale, as assessed among Indian healthcare workers, 2020 (N=662)

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.729 ** | 0.432 ** | 0.400 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.177 ** | 0.124 ** | 0.072 | 0.233 ** | 0.226 ** | 0.157 ** | |

| 2 | 0.729 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.449 ** | 0.469 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.232 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.090 * | 0.252 ** | 0.275 ** | 0.179 ** | |

| 3 | 0.432 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.668 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.591 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.290 ** | 0.124 ** | 0.052 | 0.265 ** | 0.239 ** | 0.157 ** | |

| 4 | 0.400 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.668 ** | 0.632 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.273 ** | 0.164 ** | 0.079 * | 0.256 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.227 ** | |

| 5 | 0.373 ** | 0.449 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.632 ** | 0.600 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.137 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.285 ** | 0.224 ** | |

| 6 | 0.398 ** | 0.469 ** | 0.591 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.600 ** | 0.413 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.181 ** | 0.153 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.279 ** | 0.255 ** | |

| 7 | 0.236 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.413 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.152 ** | |

| 8 | 0.177 ** | 0.232 ** | 0.290 ** | 0.273 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.135 ** | 0.120 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.243 ** | |

| 9 | 0.124 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.124 ** | 0.164 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.181 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.135 ** | 0.602 ** | 0.327 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.094 * | |

| 10 | 0.072 | 0.090 * | 0.052 | 0.079 * | 0.137 ** | 0.153 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.120 ** | 0.602 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.287 ** | 0.125 ** | |

| 11 | 0.233 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.256 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.327 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.185 ** | |

| 12 | 0.226 ** | 0.275 ** | 0.239 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.285 ** | 0.279 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.287 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.242 ** | |

| 13 | 0.157 ** | 0.179 ** | 0.157 ** | 0.227 ** | 0.224 ** | 0.255 ** | 0.152 ** | 0.243 ** | 0.094 * | 0.125 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.242 ** |

Table 2

Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation for the COVID-19-related stigma scale as assessed among Indian healthcare workers, 2020 (N=662)

DISCUSSION

COVID-19-associated stigma among healthcare workers has been well-documented worldwide9. Studies have shown a significant association of stigma with perceived stress, job satisfaction, and burnout5-8,10. There are only a few scales to assess COVID-19-related stigma among healthcare workers. The COVID-19 stigma scale prepared in this study, as an extrapolation of the MERS scale, was found to be valid for administration among healthcare workers for COVID-19.

The rate of stigma among healthcare workers in the present study was 61.6%. This study results are similar to other Indian studies exploring COVID-19-related stigma using different scales. A recent study from India explored social stigma of COVID-19 experienced by frontline healthcare workers in a department of anesthesia and critical care, using a modified Berger HIV stigma scale and found that around 56.6% reported a severe level of COVID-19-related stigma11. However, the rate of stigma in the present study is significantly higher than the reported rate from other Asian countries. A study from Indonesia assessing COVID-19-related stigma among healthcare workers from 12 hospitals across the country and found that around 21.9% of the respondents had stigma associated with COVID-1912. Another study from Egypt reported that 31.2% of participants reported severe levels of COVID-19-related stigma13. The higher prevalence of COVID-19-associated stigma among healthcare workers suggests that there is a need to have policies to address this significant public health concern, as stigma is shown to increase stress and burnout among healthcare workers.

Validation of scales to explore COVID-19-related stigma among COVID-19 patients has been performed in previous studies. A recent study from Tunisia explored COVID-19-related stigma among COVID-19 patients after quarantine using a new scale adapted from the 12-item HIV stigma scale and found that the new scale had good internal consistency with a global Cronbach α=0.91 and values of 0.94, 0.93, and 0.98 for social stigma, negative self-image, and disclosure concerns, respectively14. Another similar study from India also adapted the HIV Stigma Scale to develop a new scale to assess COVID-19 stigma, and found that the new scale had moderate-to-good internal consistency (with Cronbach α>0.6)15. However, there are only limited studies that have validated a COVID-19-related stigma scale among HCWs. A recent study from Japan developed and validated a new scale exploring the COVID-19-related stigma scale among HCWs. The new scale (18-items) showed high reliability for all factors (Cronbach α=0.970) and the coefficients for the sub-scales ‘personal stigma’, ‘concerns of disclosure and attitude’, and ‘family stigma’, were 0.940, 0.943, and 0.955, respectively16. Another group of researchers from the Middle East also developed and validated COVID-19 stigma scale to be used among HCWs working with COVID-19 patients. The 27-item scale showed good reliability (Cronbach α=0.786)17.

All the indications from various parts of the world are that the COVID-19 pandemic is not yet over, as it transitions to its more endemic phase and there are realistic chances for the emergence of newer variants of the COVID-19 virus. Considering the deleterious impact of stigma on mental health of HCWs and their quality of work, this scale could be used to detect this issue early among Indian HCWs, so that proper stigma reduction strategies can be implemented at the institutional and national level.

Limitations

The study results should be viewed in light of some limitations. First, the online survey methodology of this study might have influenced the study results, due to sampling bias. Second, the survey was conducted over a larger time frame (4 months), which might have influenced the stigma levels among HCWs. Finally, comparisons with similar studies were limited due to the scarcity of studies focusing on validating a COVID-19 stigma scale for HCWs.

CONCLUSIONS

Healthcare workers from India had significant COVID-19-related stigma during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic and the present COVID-19-associated stigma scale has good convergent construct validity and high reliability to study COVID-19-associated stigma among healthcare workers.